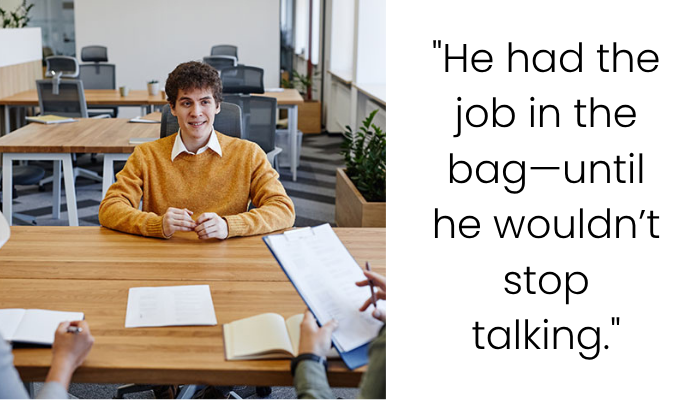

AITAH for Telling a Job Candidate to ‘Shut Up’ During an Interview?

In this striking story, OP—a technical interviewer for a high-stakes software engineering role—recounts an interview gone dramatically off the rails. The candidate had an exceptional resume and was considered a near lock for the position. However, once the interview began, things unraveled. The candidate delivered an unbroken monologue for several minutes, repeatedly ignored follow-up questions, and overrode both OP and a colleague when they tried to engage. Despite several polite attempts to redirect him, the candidate continued dominating the conversation, even interrupting responses to his own questions.

Eventually, after exhausting all conventional cues, OP firmly told the candidate, “You really have to shut up and listen,” delivering a pointed message about the importance of communication and receptiveness in professional environments. Though OP rejected the candidate outright in the moment, he’s now reflecting on whether the bluntness of his words crossed a line—even though the core issue was the candidate’s inability to listen.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Interviewing for a new job can be intimidating, no matter how brilliant you are at what you do

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Many things can ruin your chances, but for this guy it was his mouth that just couldn’t seem to keep shut

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Technical interviews are not only about assessing hard skills—they’re crucibles of soft skill evaluation, especially in roles requiring collaboration, feedback integration, and teamwork. In this post, OP’s dilemma speaks directly to a common challenge in recruitment: when an otherwise stellar candidate flounders due to poor interpersonal dynamics.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

💬 The Cost of Monologuing: Why Listening Is Crucial

In professional interviews—particularly for roles in engineering, design, and product management—interpersonal listening is as critical as the ability to code or architect systems. Research from Harvard Business Review (2016) shows that companies increasingly prioritize emotional intelligence and “collaborative communication” in technical roles, because these skills determine long-term team effectiveness.

A candidate who monopolizes the conversation, ignores cues, and talks over others demonstrates a lack of situational awareness—what psychologists refer to as low cognitive empathy, or the ability to perceive and appropriately respond to others’ intentions and emotions in real time.

In OP’s case, the candidate’s repeated behavior wasn’t just a stylistic quirk; it actively prevented the panel from assessing key competencies like collaboration, adaptability, and responsiveness. These are essential in agile environments where engineers must incorporate feedback, negotiate timelines, and explain their logic to both technical and non-technical peers.

🛑 Where Did It Go Wrong?

Let’s break down the interviewer’s progression:

- Initial patience: OP and the team gave the candidate room to introduce himself, assuming initial nerves or cultural differences might be factors.

- Attempted re-engagement: Follow-up questions were asked multiple times, only to be delayed or ignored.

- Efforts to redirect: Even when trying to wrap up politely, the candidate returned to his own narrative.

- Final line drawn: The “shut up” moment—blunt but arguably necessary to regain control and conclude the session.

OP’s phrasing was unorthodox, but not malicious. It’s clear the intent wasn’t humiliation—it was a final effort to deliver actionable feedback the candidate might not hear elsewhere.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Still, professionals in hiring roles are held to a higher standard. There’s a difference between being firm and being disrespectful, even under stress. The phrase “you really have to shut up” is jarring—even if justified—because it flips the power dynamic. At that point, OP moved from interviewer to judge and disciplinarian, which can be perceived as unprofessional, regardless of context.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

🔄 Cultural and Neurodivergent Considerations

It’s worth considering whether the candidate might have had cultural or neurodivergent communication patterns that affected his behavior. In some cultures, uninterrupted speech is a sign of respect and thoroughness. Similarly, individuals on the autism spectrum or with ADHD may struggle with conversational turn-taking or detecting social cues under pressure.

That said, such behaviors are not a free pass. In high-functioning professional environments, learning to adapt and respond is essential. If this candidate had shared a communication preference or needed a more structured format, the panel might have adapted. But in the absence of that, the burden of awareness and regulation falls on the speaker.

It’s also important to note that OP and team gave ample opportunity for course correction. This wasn’t a one-time interruption—it was a pattern sustained across multiple questions and over 15 minutes of interview time.

💼 Could the Feedback Have Been Delivered Differently?

Yes—and OP acknowledges this. Here are alternative ways OP could have handled it:

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

- Post-interview feedback: Let the interview end more gently, then provide detailed feedback in writing or through HR.

- Structured interruption: “John, I’m going to pause you there because we really want to dive into some specific questions. I’ll give you a chance to wrap up at the end.”

- Use of time checks: “We’re on a tight schedule, and we want to ensure we cover everything. Can you summarize that last point in one or two sentences?”

While “shut up” was likely said in exasperation rather than malice, it risks undermining the professionalism of the interviewer—even if the candidate had been disrespectful.

🧠 Teaching Moment or Power Move?

The final line—“You had a 99% chance of getting this job… now it’s zero”—was intended as a teaching moment. But it could be seen as unnecessarily punitive. Even well-meaning feedback, if delivered in anger or without tact, can damage both the interviewer’s credibility and the company’s reputation.

That said, candidates who behave this way rarely get honest feedback. Many would be ghosted or quietly rejected with a generic HR email. OP at least gave direct insight that the candidate might use to improve. If he truly reflects on the experience, he may become more self-aware and coachable.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

But OP must also reflect on the broader role they play—not just in evaluating talent but in shaping a fair and compassionate interview experience. A great candidate can have a bad day. A coachable one can turn it around. And sometimes, an interviewer’s role is to guide, not just screen.

People were torn and some needed more info before coming to a conclusion

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below