My Neighbor Kept Parking in My Driveway Due to “Disability”—I Had Her Car Towed

In this neighborhood conflict-turned-ethical dilemma, the original poster (OP) finds themselves in an uncomfortable battle over property rights versus perceived compassion. After purchasing a new home, OP discovers that the previous owner had allowed a neighbor—described as significantly overweight and claiming mobility limitations—to park in his private driveway. However, this informal arrangement was never communicated to the buyer. Upon moving in, OP immediately found the neighbor’s SUV occupying their driveway, blocking movers, and later, blocking OP themselves. Repeated requests to cease the behavior were met with resistance and excuses, culminating in the OP having the vehicle towed after multiple violations. While OP eventually secured their driveway with a lockable fence, they are now facing social backlash from the neighbor and at least one other resident, as well as moral judgment from their own mother.

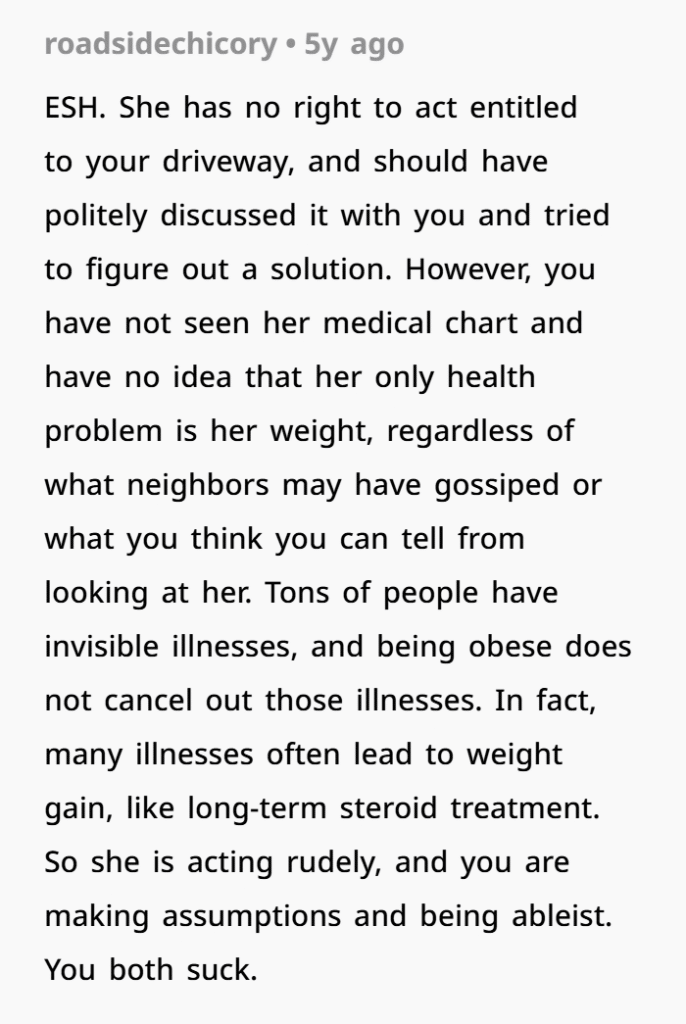

The question posed is clear: is OP in the wrong for asserting their property rights, or does the neighbor’s physical limitations and precedent set by the previous homeowner give her a reasonable expectation of continued access?

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Having good neighbors is a blessing. However, the reality is that some folks are very bad at communicating and will ignore even basic boundaries

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

One person, who had just moved into the area, shared how a neighbor of theirs felt entitled to their driveway. She wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Property Rights, Disability Law, and the Slippery Slope of Informal Agreements (1000 Words)

This situation reveals a common tension in residential communities—informal agreements made by previous owners that have no legal standing, but carry social expectations, especially when layered with issues like disability, limited parking, and perceived kindness.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

1. Legal Ownership and Use of Private Property

From a purely legal standpoint, OP is on solid ground. In most jurisdictions, a residential driveway is considered private property. Ownership of that property transfers completely to the buyer upon purchase of the home, and any previous verbal arrangements made by the prior owner do not carry over to the new owner unless formalized in the contract (e.g., a written easement or lease agreement). Since no such agreement was mentioned, the neighbor’s continued use of the driveway after OP moved in constitutes trespassing.

Towing laws vary by region, but in many states, including California and Texas, property owners have the right to have unauthorized vehicles removed from their private driveways. In this case, the OP took reasonable steps before calling a tow company—issuing repeated verbal requests, allowing time for compliance, and only taking enforcement action after multiple infractions.

2. Disability vs. Health Limitation: A Critical Legal and Ethical Distinction

The most contentious point here is the neighbor’s claim of disability. OP, somewhat controversially, uses quotation marks around “disabled,” suggesting skepticism about the legitimacy of the neighbor’s condition. The neighbor is described as “really, really overweight,” and while OP questions whether this qualifies as a disability, the answer—legally and ethically—is complex.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines a disability as a “physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.” This includes conditions like morbid obesity only when it is the result of a physiological disorder (e.g., hypothyroidism, metabolic disease). However, if weight alone is the issue, courts have been split on whether it constitutes a protected disability under the ADA. A 2019 ruling by the Washington Supreme Court in Taylor v. Burlington Northern Railroad held that obesity could be considered a disability, even without an underlying medical condition—opening the door for broader interpretations. But this does not automatically entitle someone to use private property without consent.

Furthermore, even under the ADA, reasonable accommodations must not impose an undue burden on others. Expecting a neighbor to sacrifice their private driveway, especially without formal request or documentation, far exceeds what the law requires of a private citizen.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

3. The Ethics of Accommodation and “Inherited Kindness”

Legality aside, a larger issue here is one of communal expectation and empathy. The neighbor had grown accustomed to an arrangement that worked for her, and the transition of ownership disrupted what she saw as an accessibility tool. But this brings us to a moral dilemma: how much are homeowners expected to uphold the informal goodwill of previous occupants?

This is akin to “inherited kindness”—a social expectation that just because a predecessor was generous, the current occupant must also be, regardless of the burden. That’s a dangerous precedent to set. Generosity, by definition, must be voluntary, not enforced or expected. The neighbor’s assumption that the arrangement would continue without conversation, consent, or even a proper introduction is not just presumptive—it’s entitled.

Empathy for physical limitations is important, but empathy goes both ways. The OP had to chase down a stranger multiple times, interrupt their own moving process, and endure confrontation in order to reclaim their own property. That experience is emotionally draining and, over time, breeds resentment rather than goodwill.

4. Urban Infrastructure and the Crisis of Parking Scarcity

What makes this issue even more relatable is the context of parking scarcity—a common problem in urban and even suburban areas. A lack of accessible street parking disproportionately affects those with mobility challenges, the elderly, and working-class individuals with limited flexibility. That said, it is the city or municipality’s responsibility to address these issues, not individual homeowners.

Solutions could include:

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

- Applying for a designated accessible parking spot through the city.

- Petitioning for more resident-only or time-limited zones.

- Seeking out community shuttle services for mobility-impaired residents.

None of these, however, justify unilateral use of someone else’s property.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

5. Dealing with Social Fallout: “The Bad Neighbor” Narrative

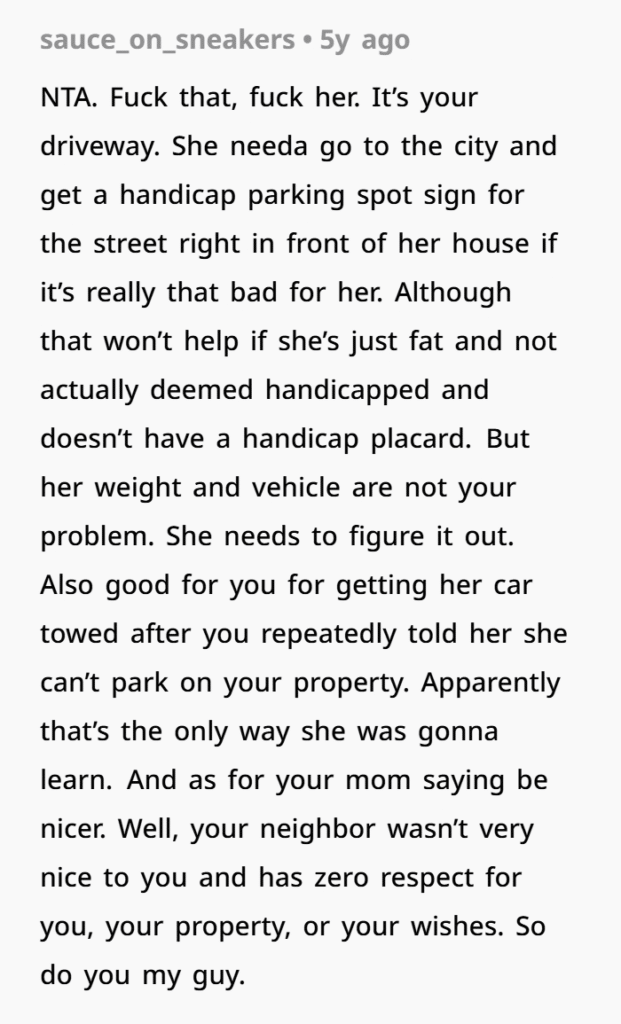

After OP had the SUV towed and installed a locking fence, the neighbor began giving them dirty looks—and another neighbor joined in. This underscores how quickly community dynamics can shift based on perceived kindness or lack thereof.

OP is now fighting not just a logistical battle, but a narrative one. They’re at risk of being labeled “the bad neighbor,” even though their actions were justified. This is a classic case of optics vs. reality—where those uninvolved may see only the result (an upset woman, a locked fence) and not the repeated breaches, stress, and disrespect OP experienced.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

The challenge here is that many people emotionally side with visible struggle (i.e., someone who is visibly struggling to walk) even if the logic or fairness isn’t on their side. It may be helpful for OP to clarify the situation privately if other neighbors bring it up—but they are under no obligation to do so.

As the story went viral, the author of the post answered people’s questions and shared more details

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below