13 Surprising Facts About Armadillos You Probably Didn’t Know

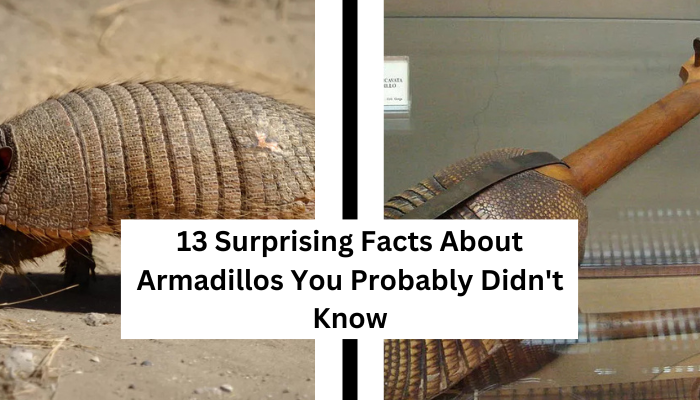

Did you know that the word “armadillo” comes from the Spanish phrase meaning “little armored one”? These fascinating creatures, known for their tough, shell-like armor, are truly among the most unique animals in the world. What’s even more impressive is that their protective covering is made of bony plates coated with keratin—the same protein found in human hair and nails.

Armadillos belong to a remarkable group of mammals native to South America, with around 20 different species that showcase an array of sizes, behaviors, and adaptations. From tropical rainforests to dry grasslands, South American wildlife is home to this incredible species that continues to captivate scientists and nature lovers alike.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

But not all armadillos are thriving. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), two armadillo species are currently listed as vulnerable, five are classified as near threatened, and another five fall under the “data deficient” category—meaning there isn’t enough information to determine their risk level, though they’re likely in danger. These figures highlight the growing concern surrounding armadillo conservation status and their future in the wild.

In 2016, scientists made a significant breakthrough by reclassifying the greater long-nosed armadillo into three distinct species. However, these newly identified species have not yet been thoroughly evaluated, raising further questions about their conservation needs.

While armadillos may seem like bizarre, prehistoric creatures, their evolutionary traits, survival mechanisms, and ecological roles make them worthy of deeper exploration. Below, we’ve gathered 13 fascinating facts about armadillos that go beyond the basics—highlighting not just their biology but also their importance in wildlife conservation and ecological research.

Whether you’re a student, a wildlife enthusiast, or simply someone with a love for nature, these surprising armadillo facts will open your eyes to one of the planet’s most intriguing—and underappreciated—animals.

1. Only One Armadillo Species Is Found in the United States

Robert Nunnally / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

The nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) holds a fascinating position in North American wildlife as the only armadillo species to have successfully migrated to the region. Originally native to the humid subtropical areas of the southern United States, its range has steadily expanded over the years. Today, these surprisingly adaptable animals can be spotted as far north as Illinois and Nebraska—a shift that underscores the effects of climate change on wildlife.

This northward movement is believed to be largely influenced by warmer winter temperatures, which allow armadillos to survive in areas that were once too cold for them to inhabit. As wildlife migration due to climate change continues to shape ecosystems across North America, the expanding presence of the nine-banded armadillo may bring unexpected changes to local biodiversity and habitats.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

One of the most intriguing facts about nine-banded armadillos is their unusual method of reproduction. These mammals give birth to genetically identical offspring through a rare process known as polyembryony. In this process, a single fertilized egg splits into four separate embryos, each developing into an identical pup. This unique reproductive strategy is exclusive to the Dasypus genus and poses fascinating questions about genetic diversity in animals and how such a method affects survival in changing environments.

But their surprises don’t end there. Despite their seemingly slow and armored appearance, nine-banded armadillos are known for their remarkable defense mechanism—a vertical leap of up to 3–4 feet when startled. This quick reaction helps them avoid predators, though it often surprises onlookers even more than it does their would-be attackers. It’s one of those quirky animal behaviors that makes the armadillo all the more endearing—and intriguing—from a biological standpoint.

As climate change reshapes the natural world, the nine-banded armadillo’s expanding habitat and rare adaptations provide valuable insights into how species evolve and adapt in real time. Whether you’re studying climate-driven animal migration or simply enjoy learning about unusual creatures, the armadillo is a perfect example of nature’s complexity and resilience.

2. Brazilian Three-Banded Armadillos Are Lazarus Species

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

The Brazilian three-banded armadillo (Tolypeutes tricinctus) stands as a powerful symbol of both nature’s resilience and the urgent need for wildlife conservation efforts. Once presumed extinct, this remarkable species made a stunning return in 1988 when researchers discovered scattered populations still surviving in the wild. Animals that reappear after being considered lost are known as Lazarus species, a term inspired by the biblical story of Lazarus rising from the dead. The armadillo’s unexpected comeback renewed hope among conservationists and emphasized the value of ongoing research in uncovering the hidden wonders of the natural world.

However, the fight to protect the Brazilian three-banded armadillo is far from over. Currently listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and endangered in Brazil, this species remains at serious risk. Its exact population size is unknown due to its secretive, nocturnal habits, making it extremely difficult to track and study in the wild.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

One of the primary threats facing this endangered animal in Brazil is habitat destruction. The dry forests and scrublands that serve as its natural habitat are being rapidly cleared to make way for large-scale soybean and sugarcane plantations. These agricultural activities not only eliminate crucial ecosystems but also fragment remaining habitats, making it harder for small populations to reconnect and survive.

Another growing concern is the illegal wildlife trade. The Brazilian three-banded armadillo is often hunted for its distinctive, armor-like shell, which can be sold on black markets, and it’s also targeted for the exotic pet trade. This type of poaching activity further reduces already fragile populations and pushes the species closer to extinction.

The Brazilian three-banded armadillo serves as a heartbreaking reminder of how quickly species can decline due to human-induced threats. Yet, it also represents hope—a second chance to make things right. Protecting endangered species like this one requires immediate action, including preserving its natural habitat, curbing poaching, and promoting sustainable land-use practices.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Through combined efforts in research, education, and conservation, we can help ensure that the Brazilian three-banded armadillo not only survives—but thrives—as a living example of nature’s incredible ability to endure against the odds.

3. Giant Glyptodonts Are The Armadillo’s Extinct Kin

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Glyptodonts were massive, prehistoric mammals that looked like dinosaur-sized armadillos, complete with an impenetrable shell of bone. These ancient creatures roamed the Earth long before humans and were once considered evolutionary outliers—until 2016, when scientists made a groundbreaking discovery by classifying glyptodonts as a subfamily of modern armadillos. This remarkable find reshaped our understanding of the evolution of armadillos, revealing a deep-rooted connection between these ancient giants and their small, armor-plated descendants.

Glyptodonts first emerged around 35 million years ago, during the late Eocene epoch, and were part of the ice age megafauna that once dominated prehistoric landscapes, particularly in what is now South America. Despite their size—some weighed up to two tons—and their formidable bony carapace, glyptodonts could not withstand the environmental and ecological changes at the end of the last ice age.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

A major factor in their extinction was the impact of early human activity on wildlife. As humans spread across the Americas, they began hunting glyptodonts for their meat. Their massive shells didn’t just serve as protection—they were also repurposed by humans to build shelters and other structures, accelerating the decline of this iconic species. This interaction is a striking example of human impact on animal extinction, particularly during the late Pleistocene era.

While glyptodonts themselves vanished, their modern armadillo relatives managed to survive and adapt, thanks to their smaller size and more flexible lifestyle. Their resilience stands as a testament to the adaptability of this unique group of animals.

Glyptodonts remain one of the most fascinating prehistoric mammals of South America, offering valuable insights into evolutionary biology, extinction events, and the deep connections between ancient species and their modern counterparts.

4. Armadillos Sleep Up to 16 Hours Each Day

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Armadillos are primarily nocturnal animals, carrying out the bulk of their daily activities—like foraging, feeding, burrowing, and mating—under the cover of darkness. During the daylight hours, they typically retreat to their underground homes, where they can sleep for up to 16 hours a day. These burrows play a crucial role in armadillo survival, offering protection from both predators and extreme temperatures.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

What makes armadillo burrows especially interesting is their unexpected use by other animals. While armadillos are mostly solitary and don’t often share their burrows with members of their own species, they have been known to cohabitate with other wildlife such as snakes, tortoises, and even rats. This makes them important contributors to the underground ecosystem, offering temporary shelter to a variety of animals.

When awake, armadillos are impressively active. Their foraging habits are among the most intense in the mammal world—only two marsupial species and ground squirrels are known to spend more time searching for food. This relentless behavior is driven by their high metabolic rate, which requires a steady intake of energy-rich food.

The armadillo diet consists primarily of insects, small invertebrates, and some plant matter, making them effective natural pest controllers. Their sharp claws and sensitive snouts help them locate food underground, often turning over soil in search of ants, termites, and beetle larvae.

From their nighttime behavior to their role as burrowing animals, armadillos are a fascinating example of how mammals adapt their routines to survive and thrive in various environments.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

5. Armadillos Spread Leprosy

Armadillos are more than just unique, armor-plated creatures—they’re also the only known nonhuman animals capable of transmitting leprosy, now more accurately referred to as Hansen’s disease. This surprising link is due to the armadillo’s unusually low body temperature, which provides a perfect environment for Mycobacterium leprae, the bacterium responsible for the disease, to survive and multiply.

Researchers believe armadillos likely contracted Hansen’s disease from humans during the 15th century, when European explorers brought leprosy to the Americas. Since then, the bacteria have continued to circulate among wild armadillo populations, particularly in the southern United States and parts of Central and South America.

But can humans get leprosy from armadillos? Yes—though it’s rare. Transmission can occur through direct contact, such as handling or consuming undercooked armadillo meat, or in some cases, inhaling airborne particles from armadillo feces. While Hansen’s disease is treatable with antibiotics, early diagnosis is crucial to prevent long-term complications.

This connection highlights the growing importance of understanding zoonotic diseases, which are illnesses that can be passed from animals to humans. As human-wildlife interactions increase, so too does the risk of disease transmission from animals, emphasizing the need for public health awareness, responsible hunting practices, and wildlife disease prevention efforts.

Whether you’re a hunter, researcher, or wildlife enthusiast, it’s essential to take precautions when handling armadillos or entering environments where they live. With proper education and care, we can better manage the risks while continuing to learn from these fascinating animals.

6. Only 2 Species of Armadillo Are Capable of Rolling Into a Ball

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

A common myth about armadillos is that they can curl up into tight balls and roll away from predators. While this image is often portrayed in cartoons and popular culture, it’s not accurate for most armadillo species. So, can armadillos roll into a ball? The answer is yes—but only two species in the entire armadillo family can actually do this.

The Brazilian and Southern three-banded armadillos (genus Tolypeutes) are the only ones capable of curling into a nearly perfect ball. Thanks to their uniquely segmented, flexible shell, these armadillos can tuck in completely, using their tough armor to shield themselves from predators. This behavior acts as a powerful defense mechanism, making them nearly impenetrable when threatened.

All other armadillo species, however, have much more rigid armor with overlapping plates that prevent them from achieving this full-body curl. Instead of rolling up, they rely on alternative ways to protect themselves—like burrowing quickly, hiding underground, or even using bursts of surprising speed to flee from danger.

Understanding the truth behind this popular belief not only clears up confusion but also highlights the diverse adaptations of armadillos. The curling ability of the three-banded armadillo is a remarkable evolutionary trait, making them one of the most fascinating members of this ancient mammalian lineage.

If you’re intrigued by wildlife myths debunked or want to learn more about how armadillos defend themselves, this is a great example of how nature often surprises us with both truth and fiction.

7. The Giant Armadillo Is the Largest of the Species

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

The giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus) holds the title of the largest species of armadillo on Earth. In the wild, these powerful creatures can weigh anywhere between 45 and 130 pounds, though some in captivity have reached an astonishing 176 pounds. Measuring nearly 5.9 feet in length, including their tail, the giant armadillo is a true heavyweight of South American wildlife.

One of the most distinctive features of the giant armadillo is its 8-inch middle front claws—the longest claws of any living mammal. These massive tools aren’t just for show—they’re perfectly adapted for digging into the soil in search of ants, termites, and other small invertebrates, which make up the bulk of the giant armadillo’s diet.

But despite their size and specialized adaptations, giant armadillos are facing growing threats in the wild. They are currently listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), with their population numbers in decline. The main threats include habitat destruction due to deforestation, especially for agriculture and cattle grazing, and hunting for bushmeat in rural areas.

Adding to the pressure is the illegal wildlife trade, where giant armadillos are sometimes captured and sold in black markets, either as exotic pets or for their unique body parts. This dangerous combination of factors makes the species highly susceptible to population fragmentation and long-term extinction risk.

Protecting the giant armadillo’s natural habitat and reducing human impact is crucial to their survival. Conservation initiatives focusing on habitat preservation, anti-poaching enforcement, and public education are essential to give this iconic species a fighting chance.

As one of the most enigmatic yet endangered mammals of South America, the giant armadillo serves as a powerful reminder of what’s at stake when human activity disrupts fragile ecosystems.

8. The Pink Fairy Armadillo Is the Smallest of the Species

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

The pink fairy armadillo (Chlamyphorus truncatus) is one of the most unusual and rare mammals on Earth. Recognized for its soft pink armor and tiny frame, this species holds the distinction of being the smallest armadillo in the world, measuring just 4 to 6 inches long and weighing only around 3.5 ounces. Despite its size, the pink fairy armadillo is a master digger. It features a distinct vertical plate on its rump, which it cleverly uses to backfill its burrows, sealing off tunnels for protection from predators.

Native to the sandy plains and scrubby grasslands of central Argentina, this nocturnal and elusive animal is rarely seen, even by researchers. As a result, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the species as “data deficient”, meaning there’s not enough available information to accurately determine its conservation status. However, current trends suggest that it may be at risk of becoming near threatened, or worse.

The primary threat to the pink fairy armadillo is the ongoing destruction of its natural habitat, largely due to agricultural expansion, land development, and human encroachment. As farming and cattle grazing continue to alter the landscape of central Argentina, the armadillo’s fragile habitat becomes increasingly fragmented and inhospitable.

Another alarming concern is the impact of the illegal exotic pet trade. With its rise in popularity on social media platforms, this unique species has become a target for wildlife trafficking. Unfortunately, most individuals captured for the pet trade do not survive long in captivity, as the species is extremely sensitive to environmental stress and specific care requirements.

The plight of the pink fairy armadillo serves as a critical example of how viral trends and habitat loss can endanger even the smallest and most secretive creatures. Conservation efforts are urgently needed, including public education, habitat preservation, and stronger regulations to prevent illegal wildlife trade.

As one of the most endangered animals of Argentina, the pink fairy armadillo reminds us that size doesn’t determine importance—and that even the tiniest species deserve protection.

9. This Amadillo Screams to Warn Off Predators

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

The screaming hairy armadillo (Chaetophractus vellerosus) isn’t just named for its tough armor and unusually hairy body—it’s also famous for its shocking vocal abilities. When threatened, this armadillo lets out high-pitched, alarm-like screams, making it one of the most vocal and dramatic members of the armadillo family. These piercing vocalizations serve as an effective defense mechanism, startling predators and deterring threats before physical confrontation becomes necessary.

This species’ screeching sounds have helped it stand out in the world of mammals and are a key feature often highlighted in screaming hairy armadillo facts. Found in regions of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Paraguay, it thrives in dry, arid environments such as grasslands and scrublands—areas where it can dig burrows and forage for insects, plants, and small vertebrates.

Despite its unique behaviors and adaptations, the screaming hairy armadillo isn’t immune to human threats. Hunting for its meat and carapace remains an ongoing issue in some regions. However, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently classifies the species as “Least Concern”, thanks to its relatively stable population and broad geographic range.

Still, as with many species, ongoing habitat loss and hunting impact on wildlife mean that conservationists continue to monitor population trends. Maintaining this species’ status requires proactive efforts to prevent excessive trapping and ensure its habitat remains protected.

The screaming hairy armadillo is yet another example of the diverse wildlife in South America that blends fascinating adaptations with a need for mindful conservation. Its distinctive vocalizations, resilient nature, and ecological role make it a standout species worth both studying and protecting.

10. Pichi Are the Only Armadillo Species to Hibernate

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

While armadillos are known for their relaxed lifestyles, the pichi armadillo (Zaedyus pichiy) takes rest to the next level—by actually hibernating during winter. Unlike most of its relatives, the pichi is the only armadillo species known to undergo true hibernation, making it a fascinating subject in studies on animal survival strategies.

Before winter sets in, the pichi builds up fat reserves and retreats to a burrow, where it enters a state of deep hibernation. During this time, its body temperature drops dramatically from a typical 95°F to just 58°F, allowing it to conserve energy and survive in freezing temperatures when food becomes scarce. This extreme adaptation is vital for enduring the harsh winters of the Patagonian Steppe and Pampas regions of South America.

But the pichi’s energy-saving skills don’t end there. Even outside of winter, it frequently enters torpor, a temporary state of reduced metabolic activity—essentially a mini-hibernation—that helps it manage energy throughout the day. This unique trait sets it apart as one of the most efficient energy conservers in the armadillo family.

Native to the windswept, arid landscapes of Patagonia, the pichi thrives in an environment where few mammals can. Its ability to hibernate and utilize torpor allows it to avoid predators, endure harsh climates, and stretch limited resources. These behaviors make it one of the most specialized examples of energy conservation in mammals.

Whether you’re fascinated by how animals survive winter or intrigued by the unique biology of Patagonian wildlife, the pichi armadillo stands out as a remarkable testament to nature’s ingenuity.

11. Some Armadillo Species Are at Risk for Extinction

While the nine-banded armadillo continues to maintain a stable and thriving population across much of North and Central America, many of its relatives are facing increasing threats. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), several armadillo species are now considered vulnerable or near threatened.

The Brazilian three-banded armadillo and the giant armadillo are both officially listed as vulnerable, reflecting their declining numbers and shrinking habitats. Other species, including the Pichi, Southern long-nosed armadillo, Northern long-nosed armadillo, Southern three-banded armadillo, and the Chacoan naked-tailed armadillo, are classified as near threatened. In addition, five more species are marked as data deficient, meaning there’s not enough research available to fully assess their risk level—though many experts believe they could be potentially endangered.

The leading threats to these endangered armadillo species are hunting and habitat destruction. Armadillos are often hunted for their meat, and some are captured for the illegal wildlife trade, where they are sold as exotic pets. However, the most pressing long-term issue is habitat loss, driven by human development and industrialization.

Deforestation, cattle ranching, and the expansion of palm oil plantations continue to destroy critical armadillo habitats, but one of the fastest-growing threats is mining. With the increasing global demand for copper—an essential metal in electronics—mining operations have expanded dramatically. This surge has led to large-scale land degradation and ecosystem fragmentation, displacing armadillos and other wildlife from their natural environments.

The impact of mining on biodiversity is especially severe, as it not only removes essential shelter and food sources but also divides habitats, making it harder for populations to interact and reproduce. As a result, isolated groups become more vulnerable to extinction.

These combined pressures emphasize the urgent need for armadillo conservation efforts. Protecting natural habitats, enforcing anti-poaching laws, and supporting sustainable land-use practices are critical steps toward safeguarding these unique creatures and the ecosystems they call home.

12. Armadillo Shells Are Used to Make Musical Instruments

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Charangos, the iconic 10-stringed instruments of the Andes, hold a special place in the vibrant musical traditions of Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, and Peru. Originally created with dried armadillo shells, charangos produced a distinctive, resonant tone that became a hallmark of traditional Andean music. The use of armadillo shells not only offered unique acoustic properties but also symbolized the resourcefulness of Indigenous communities in utilizing local materials.

However, as awareness of wildlife conservation grew and populations of certain armadillo species declined, the crafting of armadillo shell instruments became increasingly scrutinized. Today, most modern charangos are crafted from sustainably sourced wood or occasionally calabash gourds, offering a more ethical and accessible alternative that preserves the instrument’s iconic sound without harming wildlife.

Armadillo shells were also historically used to create matracas—handheld carnival rattles played during festivals and celebrations across the Andes. These rattles, while culturally significant, sparked conservation concerns as demand for armadillo shells increased.

In response, many South American countries introduced wildlife protection laws to curb the trade and use of animal-derived instruments. Notably, in 2015, legislation was passed making it illegal to sell or possess new armadillo shell matracas, marking a key step toward reducing animal exploitation and promoting more sustainable practices in cultural traditions.

These shifts reflect a broader movement to balance cultural heritage with environmental responsibility. As artisans and musicians embrace eco-friendly materials, the legacy of traditional instruments like the charango continues to thrive—this time, in harmony with nature.

13. Armadillos Are Good Swimmers

Danita Delimont / Gallo Images / Getty Images

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

Although often associated with dry, land-based habitats, armadillos are surprisingly skilled swimmers. These fascinating creatures can hold their breath for 4 to 6 minutes, allowing them to navigate aquatic environments with ease. When crossing shallow streams, armadillos use their powerful legs to walk along the riverbed, while in deeper waters, they gulp air to inflate their stomachs and intestines, increasing buoyancy. This lets them float and “dog paddle” across rivers—a unique and rarely observed behavior among land mammals.

This aquatic adaptation has been crucial to the range expansion of armadillos, particularly the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), one of the most widespread species in the Americas. As this species migrated northward from Central America into the United States during the 20th century, its ability to swim across rivers and wetlands—including the Rio Grande—played a pivotal role in its success.

Today, the nine-banded armadillo’s range includes parts of Texas, the southeastern U.S., and even stretches as far north as Illinois and Nebraska. Their adaptability to various habitats, including wetlands, forests, and grasslands, is a testament to their survival strategies and the importance of behavioral flexibility in animal migration.

Understanding how armadillos adapt to new environments not only highlights their resilience but also offers valuable insight into wildlife migration patterns in response to climate change, habitat disruption, and geographic barriers. Whether walking underwater or paddling across a pond, armadillos prove that even the most unexpected animals can be remarkably versatile travelers.